Référence :

Bartel Sheenan, K. (1999). An investigation of gender differences in on-line privacy concerns and resultant behaviors. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 13 (4), 24-38

| Idée / dominante :

Les femmes sont plus inquiètes que les hommes pour la protection de leur vie privée face à différentes situations impliquant la récolte d’informations personnelles. Cependant, les hommes sont plus enclins à changer de comportement online lorsqu’ils sont inquiets pour leur vie privée. Ceux-ci peuvent adopter plusieurs types de réactions (aussi bien passives qu’actives), alors que les femmes ont un attitude plus passive et moins conflictuelle. |

Résumé :

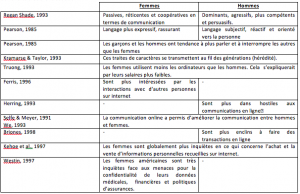

Afin de mener à bien son projet, l’auteur dresse une brève revue de la littérature, qui peut-être résumée dans le tableau ci-dessous :

L’étude cherche à définir les différences entre hommes et femmes dans leur degré d’inquiétude pour la vie privée face aux activités marketing impliquant la collecte d’informations. L’auteur cherche ensuite à établir un lien (corellation) entre le niveau d’inquiétude et le comportement.

Méthodologie : enquête soumise par e-mail à un échantillon représentatif de la population. Mesure du degré d’inquiétude face à différentes situations (15) via une échelle de Likert (7 points).

Résultats : quelques situations ont montré une inquiétude significativement plus élevée de la part des femmes pour la privacy :

– la réception d’e-mails non-sollicités

– usage secondaire des données personnelles récoltées.

– Le partage de différents types d’information

– Recevoir des e-mails d’entités inconnues

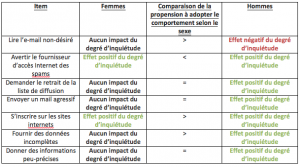

Le tableau ci-dessous répertorie les réactions de internautes (hommes et femmes), et les compare au degré d’inquiétude mesuré lors de la première partie de l’enquête.

De fait, les femmes étant globalement plus inquiètes que les hommes, ce sont ces derniers qui font réagissent le plus en termes de comportement en fonction de leur degré d’inquiétude pour leur vie privée.

| Notes d’intérêt pour la recherche en cours :

Différences d’inquiétudes entre hommes et femmes quand à l’utilisation de leurs données sur internet. Limites : Article datant de 1999, certaines données sont obsolètes et ne prennent pas en compte cette problématique dans le cadre des réseaux sociaux. Se base principalement sur le mailing et la problématique des spams (publicités d’entreprises connues ou non). |

Références :

Briones, M. (1998). Online Retailers Seek Ways to Close Shopping Gender Gap. Marketing News, 2.

Brunner, C, and Bennett, D. (1997). Technology and Gender: Differences in Masculine and Feminine Views. NAASP Bulletin, 81 (592), 46-52.

DeBare, I. (1996). Women Lining Up to Explore On-line. Sacramento Bee.

Garrubbo, G. (1998). What Makes Women Click? Advertising Age, 69 (5), 12a.

Gurak, L. J. (1995). On Bob, Thomas, and Other New Friends: Gender in Cyberspace. Computer-Mediated Communication Magazine, 2, 2.

Herring, S. (1993). Gender and Democracy in Computer-Mediated Communication. Electronic Journal of Communication, 3, 2.

Herring, S. (1994, June 27). Gender Differences in Computer Mediated Communication: Bringing Familiar Baggage to the New Frontier, keynote talk. “Making the Net *Work*: Is There Gender in Communication?” panel discussion. American Library Association annual convention, Miami.

Kramarae, C. and Taylor, H. J. (1993). Women and Men on Electronic Networks: A Conversation or a Monologue? In C. Kramarae (Ed.). Women, Infor- mation Technology, and Scholarship. Urbana, IL: Center for Advanced Study, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Nowak, G. J. and Phelps, J. (1992). Understanding Privacy Concerns: An Assessment of Consumers’ Information Related Knowledge and Beliefs. Journal of Direct Marketing, 6 (4), 28-39.

Parks, M. R., and Floyd, K. (1996). Making Friends in Cyberspace. Journal of Communication, p. 46.

Pearson, J. C. (1985). Gender and Communication. Dubuque: William C. Brown Publishers.

Regan Shade, L. (1993). Gender Issues in Computer Networking. Talk presented at Community Networking: The International Free-Net Conference, Carle- ton University, Ottawa, August 17-19.

Savicki, V., Lingenfelter, D., and Kelly, M. (1997). Gender Language Style and Group Composition in Internet Discussion Groups. Journal of Computer Mediated Communications.

Selfe, C. and Meyer, P. (1991). Testing Claims for On-line Conferences. Written Communication, 8, 162-192.

Sheehan, K., and Hoy, M. (1997). WarningSigns oin the Information Highway: An Assessment of Privacy Concerns of Online Consumers. Presented at the Association for Education inJournalism and Mass Communications Annual Conference, Chicago.

Sheehan, K., and Hoy, M. (1998). Privacy and Online Consumers: Comparisons with Traditional Consumers and Implications for Advertising Practice. Presented at the 1998 American Academy of Advertising Conference, Lexington, KY.

Speer, T. L. (1996, May). They Complain Because They Care. American Demographics, p. 00.

Sukamar, R. (1998, October 10). Managing the Market- place: Netting the Better Half. Business Today, p. 156.

Teicholz, N. (1998, October 22). Women Want It All, and It’s All Online. New York Times on the Web.

Truong, H. (1993). Gender Issues in Online Communication. BaWIT.

Turkle, S. (1988). Computational Reticence: Why Women Fear the Intimate Machine. In C. Kramarae (Ed.). Technology and Women’s Voices. New York:Routledge Kegan Paul, pp. 41-61.

We, G. (1993). Cross-Gender Communication in Cyberspace, unpublished manuscript, Simon Eraser University.

Witmer, D. and Katzman, S. (1997). Online Smiles: Does Gender Make a Difference in the Use of Graphic Accents? Journal of Computer Mediated Communication.